-

Posts

484,430 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

661

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Articles

Videos of the Month

Major Race Contenders

Blogs

Store

Gallery

Everything posted by Chief Stipe

-

Mark Mitchell is a wet. Let me guess who "some of her colleagues" are: Todd Muller - gone. Simon Bridges - still miffed he got rolled by a lightweight in Muller. Luxon - thinks he is another John Key - yeah right.

-

Of all people I thought you would be the last to buy into the media hit job!

-

50% of the horses in training are at Cambridge aren't they?

-

The more you get into the detail the more questions about the sustainability of this new Super Club emerges. For example: is there a Strathayr track anywhere else with a comparable climate that can sustain 40 race meetings a year? That's about 400 races. Or 16% of the national total. Now add another 42 race meetings (14 x 3) from the AWT'S alone that takes the total to 30%+. Then add their Turf meetings and we'll aren't we getting close to 50%+ of the races in NZ occurring at 4 locations? Ellerslie, Cambridge, Awapuni and Riccarton.

-

Correct me if I'm wrong which I'm sure a couple of people will try and do anyway..... But wasn't the Strathayr Track and the doubling of stakes contingent on getting the assets from Avondale Jockey Club? Where is that at?

-

Are you referring to Westland? How much subsidisation have they had over the years compared to Ellerslie? The Hokitika Racecourse was a community asset, built on the back of hard work by the community. It was clear that if the asset was given back to racing it wasn't going do anything for the Hokitika community nor racing on the West Coast. Good luck to Auckland - I sincerely hope that the planets align for them to achieve what they are setting out to achieve. It isn't a forgone conclusion that they will achieve their objectives but if they do then for Auckland and Waikato racing it will be great. However will it stand on it's own two feet? Will the revenue they generate from their core revenue streams pay for all the premier races that they currently have that have their stakes subsidised by the rest of the industry and pokies? Will they be expected to pay their way OR will they continue to drain revenue from elsewhere? Surely that is the key - if the Auckland Racing Club can achieve what they are proposing to do without ANY subsidisation then it might work. If not then it will distort the market further with a high cost model of production and that will not be a good outcome for NZ. For those thinking that Ellerslie is being set up to be the Hong Kong of New Zealand well if all due respect you are dreaming. The whole of NZ racing doesn't get anywhere near the total revenue generated by racing in Hong Kong. That and the fact that Hong Kong is also a closed system training facility. I don't see any horses being trained at Ellerslie anytime soon.

-

OK @JJ Flash I'll ask you the same question how will the new Auckland conglomerate help provincial racing? You know that part of New Zealand's racing infrastructure that has been its bread and butter and the arguably the reason for its success. Or are you happy for NZ racing to be centred entirely on Auckland and the Waikato? I'd love to see how this development will help racing overall. Will Auckland distribute some of the assets that they have gained on the back of the rest of the country? That would only be fair would it not?

-

Does the "greater" Auckland region extend to the Waikato? Will it assist NZ racing as a whole? With a new Strathayr track at Ellerslie how long do you think the Guineas will last at Riccarton?

-

Tell me how this helps Racing across the country? Will this new conglomerate sponsor races in the provinces? Good luck to them and it will be good for those in the Waikato and South Auckland but will it help racing anywhere else? Tesio tell us how it will? I'd really like to know.

-

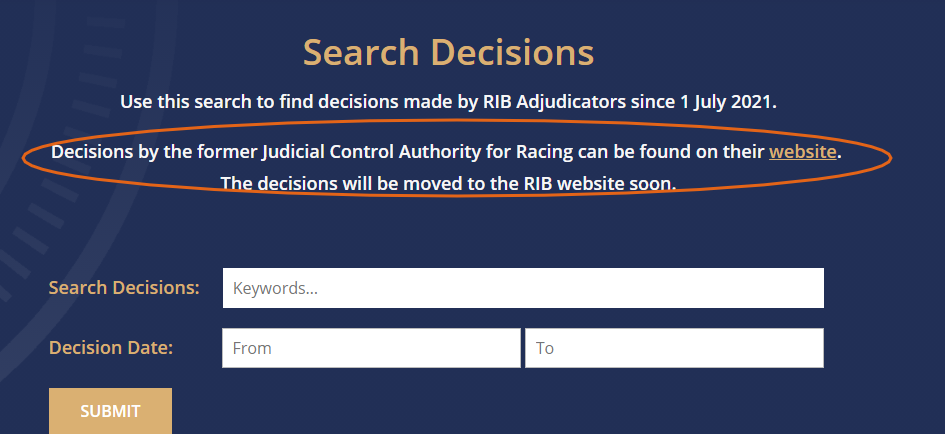

Looks like Thomarse got through to Stuff! 11:53am Joseph Johnson/Stuff Shaun Phelan agreed completely that his comments were inappropriate and added that he is himself part-Maori. (File pic) Racially disparaging comment about Māori in relation to occasionally slow race horse earns trainer $800 fine Marty Sharpe A horse trainer who referred made racially disparaging comments referring to his sometimes-slow horse has been fined $800. Shaun Phelan, who co-trains the horse BIG MIKE with his father Craig, admitted making an inappropriate comment of a racist nature when being interviewed live on Trackside TV on July 3. The remark was made when Phelan was interviewed before Race 5 at the Hawke’s Bay racecourse. In the interview he said: “Yea, as long as the track today is on that better side of slow, if it’s not the holding side -the only worry the big boy can’t get his feet. When he can’t get his feet out of the ground he just, he’s got a bit of Māori in him and doesn’t feel like having a go….” The matter was heard by the Racing Integrity Board the same day. In a recently released decision, the board said Phelan “agreed completely that what he said was inappropriate adding that he is himself part-Maori”. “The interview took place in the jockeys’ room while he was getting ready for the race, and in that situation he said “you tend to forget that phone interviews are going live on TV”,” the board said. The board said Phelan had a clear record in regard to the misconduct rule. He had been an apprentice rider and had held a jumps licence for many years. More recently he had become a licensed trainer out of Cambridge in partnership with his father. “This incident was out of character for him,” the board said. Joseph Johnson/Stuff Shaun Phelan and Upper Cut, on which he won the Grand National Open Steeplechase during The Grand National Carnival week held at Riccarton Park in 2017. (File pic) Chief stipendiary steward John Oatham said he knew of no other similar cases. The closest was a jockey who had been suspended for two days for making a racial comment to a fellow rider. Oatham said the stewards did not condone anything of a racial nature in racing and said a fine of not less than $1000 would be appropriate. The board’s ruling noted that Phelan said the penalty had to be such that neither he nor anyone else in the racing industry made the same mistake in the future. “It was a wakeup call for him to be more careful and to remember that everything can be recorded. It was not a good look for him or his business,” it said. “The comments made by Mr Phelan on live television were insensitive, inappropriate and thoughtless. Not only has this reflected poorly on him, but also on the racing industry in general,” the ruling said. The board said Phelan instantly recognised his comments were racially offensive and unacceptable. He was contrite, did not attempt to downplay his comments, and accepted that he must be held to account. He was fined $800. The board said that if Phelan had failed to recognise or understand the gravity of his comments the fine would have been greater.

-

As I said in another thread: Plus the "new" standardised fare has a higher operational cost model. It's lunacy. The news from Auckland isn't all roses either. It is only another black hole that will suck the life out of the provinces. Again Ellerslie is a dead end higher cost model proposition.

-

Plus the "new" standardised fare has a higher operational cost model. It's lunacy. The news from Auckland isn't all roses either. It is only another black hole that will suck the life out of the provinces. Again Ellerslie is a dead end higher cost model proposition.

-

Brand New Kittens Grant Roberson (wearing bright LBGT lycra) is out jogging one morning and notices little Brodie on the corner with a box. Curious he runs over to little Brodie and says, “What’s in the box kid?” Little Brodie says, “Kittens, they’re brand new kittens.” Robertson laughs and says, “What kind of kittens are they?” “They are Labour kittens” says Little Brodie. “Oh that’s cute,” he says and he goes on his way. A couple of days later Robertson is running with his buddy Chris Hipkins (wearing a face mask and a QR code emblazoned on his T-shirt) and he spies Little Brodie with his box just ahead. Robertson says to Chris, “You gotta check this out” and they both jog over to little Brodie. Robertson says, “Look in the box Chris, isn’t that cute? Look at those little kittens. Hey kid tell my friend Chris what kind of kittens they are.” Little Brodie replies, “They are ACT kittens.” “Whoa!” Robertson says, “I came by here the other day and you said they were Labour kittens. What’s up?” “Well,” little Brodie explains, “Their eyes are open now.”

-

They only reason is because they influence the number of imported races shown on Trackside AND those that are exported. I think once that the revenue split was done on domestic turnover only not on imported and exported race revenue by code. HRNZ and GRNZ leadership hasn't been too smart in fighting for a fair deal. Turnovers push $30m Betting on harness racing in this country was just short of $30m for May and June. Figures just released by the TAB show that total turnover was $13,431,339 in June, and $16,519,650 in May – a total of $29,950,989. The June figures were highlighted by the Harness Jewels at Cambridge ($2.656m) while the meeting with the highest turnover in May was Addington on May 14 ($1.550m). That meeting included the Group One Nevele R Fillies Final won by Bettor Twist. Harness-Racing-Turnover-MayJune-2021.pdf

-

And you wonder why Tasmanian Harness Racing is finishing in October.

-

Stakes Increase(?) Announcement for 2021-22 Season

Chief Stipe replied to Chief Stipe's topic in Galloping Chat

When does the grading committee pass judgement? Surely some of our Group races will be dropped down a level. That will free up some dosh for the lower classes. -

Stakes Increase(?) Announcement for 2021-22 Season

Chief Stipe replied to Chief Stipe's topic in Galloping Chat

Correct. Mid-week maiden races in OZ $25,000. They have non-tote race meetings for stakes between $5k and $12k. -

Based on what? Doing the same as this past year or so? You can't cut much more cost out so the only way to increase stakes is to increase revenue. Please don't tell me they are going to use pillaged capital assets to fund stakes! Which brings me to my next chestnut. All our major tracks need extensive renovations. Where is the funding coming from and when will the work be done? The irony is they are either closing down perfectly good racing surfaces or underutilising them. Foxton for example.

-

Very good point. I'm picking they went "OK the total pie is bigger and we will at least get the same size piece as last season". But there is no budget, no published parameters by which anyone can measure NZTR’s plan for the coming season. There is SFA on NZTR’S website other than a copy of a spreadsheet with race dates. I don't think I've ever seen so little in the way of published plans and programmes for a coming season. It all looks ad hoc. I'm wondering if Saundry is way out of his depth because he is sure as he'll making Purcell look like an extraordinary transparent and able communicator and Manager!